Into the Score: Bach B Minor Mass

Welcome to Into the Score! The videos and writings below take you into the world of J.S. Bach’s B Minor Mass. I hope these resources will help you understand and enjoy this monumental piece of music.

—RJB

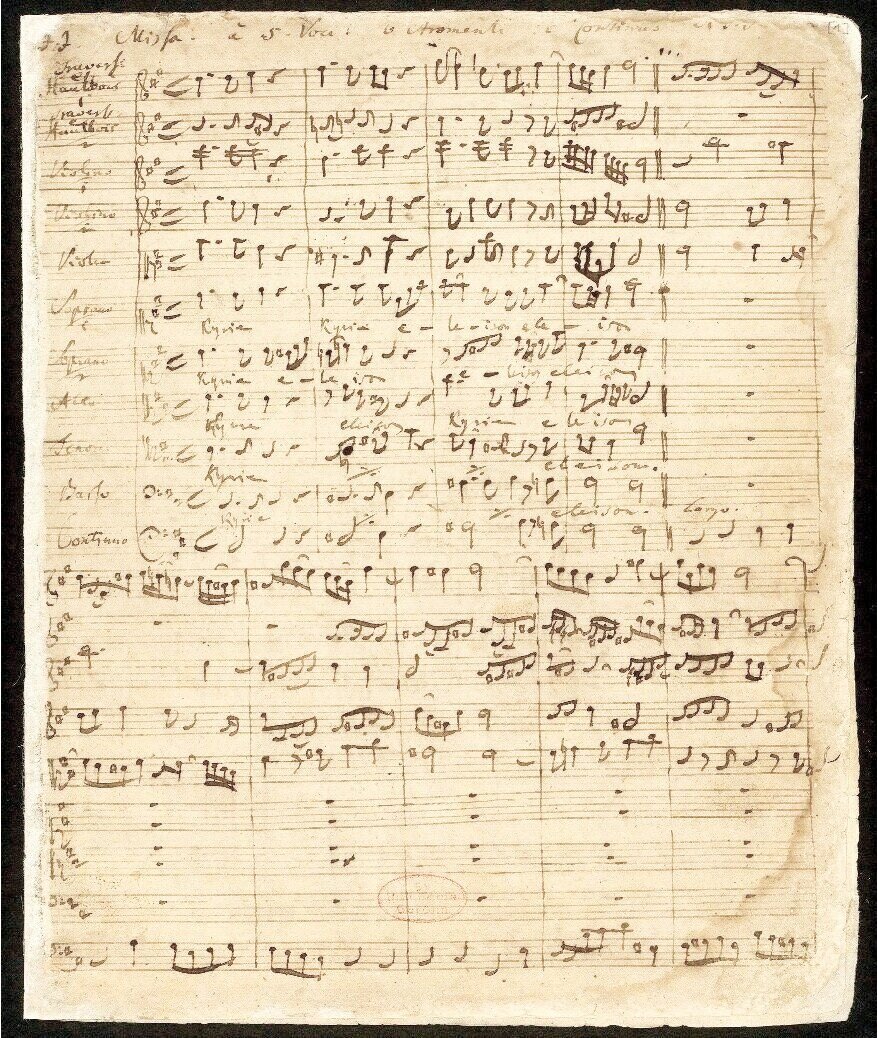

To many, the music of J.S. Bach represents the best the art form has to offer. It demands the utmost from those who attempt to play and interpret it. Embroidered with elaborate detail and rich with gold-dense harmonies, the sheer craft of it is our greatest artistic treasure. We naturally revel in the heightened sense of execution the music demands, whether we’re performing it or listening to it; the challenge becomes part of the aesthetic experience. When it builds an intricate edifice of interlocking lines atop a foundational harmonic progression, Bach’s counterpoint reveals his inner architectural genius. To see a Bach score on paper is to be dizzied by black ink; to hear a Bach score in the hands of experts is to be dazzled by the capabilities of the human mind and body. Two hundred and seventy years’ worth of musical and technological invention haven’t rendered the splendor of Bach’s creations any less brilliant.

Now, in November 2020, I find myself asking: have we ever needed Bach’s music more? Four or five years ago I wrote: “A lot of ink has been spilled about the ineffectuality (at best) or insidious impact of echo-chamber intra-enclave dialogue. Blitzes of 140-character cherry-bombs leave the mind and nerves too tattered to wage the longer battles of complex conversation. Fleeting chyron captions flash on and off before stories can be fleshed out with facts. Caustic talking-head crossfire eats away at the ideal of reasoned discourse like so much acid rain on an ancient limestone temple.” Little did I know, then! Who, anymore, has the bandwidth and energy to hear or read anything long-form amidst the noise and exhaustion? Pop songs and tweets aren’t so far apart. The just-right length of a pop hit requires just a few minutes. The formulaic structure requires us to establish expectations only to have them unfailingly confirmed in the final chorus, perhaps with an all-caps key change. The holiday music that plays seemingly everywhere this time of year palliates, too. Endless repetition and the familiarity of finite repertoire ensure easy listening.

But Bach’s music can’t be easily digested, like a candy-cane pop song; its layers are many, and its flavors are complex. Beneath the ink-speckled surfaces exists a body of work with a fascinating ability to transmit and grapple with multiple meanings. Bach’s music reconciles seemingly opposite qualities in paradoxical combinations: daunting complexity and powerful directness; abstract contrapuntal meticulousness and improvisatory ornate spontaneity; divine grandeur and worldly struggle. So often, an attempt to understand a piece of his music as one thing or another leads to the recognition that it is, of course, both things at once. Dealing with Bach’s music can resemble scientific inquiry: the more we discover, the more we realize how much more there is left to uncover.

How fortunate we are, then, that Johann Sebastian Bach, ten years into his job in Leipzig (1733), frustrated with his work situation in Leipzig, composed a Missa to present to the Dresden Court, in which he sought a position, a compendium-like setting of those two sections of the Mass Ordinary meant showcase his prowess as a composer of several styles of music. Though he didn’t get that position, at first, he did create the start of a grand and varied setting of the Mass Ordinary. Much later in life, he would return to this Missa, and add settings of the rest of the sections of the Ordinary to complete it, writing some entirely new movements and reworking some others from other decades of his life. The resulting compilation, completed in the very last years which we now call the Mass in B Minor (a title Bach never used in his lifetime), presents his most ardent plea for peace with his most essential music.

Over the course of his B Minor Mass, Bach showcases the depth and variety of his compositional craft. The first Kyrie, with its pleading, loping fugue theme, unfolds, through the plum-colored dark colors of B minor, steadily and solemnly, over its ten minutes course. It’s this sound world in my ear when I read poet Adrienne Rich’s descriptor “this antique discipline, tenderly severe.” In the jubilant “Gloria in Excelsis,” Bach depicts angel heraldry with a quick-footed dance, and peace on earth with a gentle, lulling melody accompanied by broad, graceful melismas. Like a brilliant choreographer, sends a galloping baroque dance rhythm spinning through the sections of the choir and orchestra so convincingly we can practically see them twirling and jumping and looping in dazzling coordination when we listen. The invocations of “holy, holy, holy” in the “Sanctus” circle round in great loops of triplets from various trios of parts among the chorus, evoking great billows of incense. The richly varied solo movements, which feature all the voice parts in beguiling combinations with solo instruments, remind us of Bach’s gifts as a melodist and composer of idiomatic instrumental music. By the work’s end, Bach has, through music, expressed supplication, joy, awe, wonder, sorrow, grief, and humility.

Yet as much as I stand in awe of those two hours of music, it’s the very end that really blows me away—not with its complexity, but its simplicity.

Let’s go inside the score to see why.

Listen to the Dona Nobis Pacem here, in a sublime, unhurried performance by Sir John Eliot Gardiner and the Monteverdi Choir

Summing it all up…

This final minute of music, one of the most sublime in the entire repertoire, encapsulates the endeavor: the pursuit of perfection in the earthly realm to reflect one beyond. Bach tried his best to write secular music of the highest art and sacred music worthy of the glory of God, but of course he was just a human being, in spite of his otherworldly gifts. How fortunate we are that that disparity seemed to light the fire ever burning within him. Over the course of his career, he attempted not just a “well-regulated church music,” but a well-regulated music that systematically explored the art’s many facets. Human, divine, refined, colossal, individual, corporate: Bach’s music constantly commingles these strata, and in the commotion our relationships to each other and to the world around us are revealed. How fortunate we are that he endeavored to sum his abilities as a composer of choral-orchestral music with his unparalleled Mass in B Minor. As so much of Bach’s music does, the Mass’s many moments provide the perfect soundtrack for reflection, revelation, and aspiration, as indispensable now as ever.

Click the video below to hear a complete performance of the B Minor Mass, given by the English Concert and a stellar team of soloists, led by Harry Bicket.

Sir John Eliot Gardiner, scholar and conductor, offers some thoughts about Bach’s universality.

To listen to RJB’s playlist of some of his favorite choral, instrumental, and keyboard works, “Best of Bach, click here.

by Adrienne Rich

“At a Bach Concert”

Coming by evening through the wintry city

We said that art is out of love with life.

Here we approach a love that is not pity.

This antique discipline, tenderly severe,

Renews belief in love yet masters feeling,

Asking of us a grace in what we bear.

Form is the ultimate gift that love can offer –

The vital union of necessity

With all that we desire, all that we suffer.

A too-compassionate art is half an art.

Only such proud restraining purity

Restores the else-betrayed, too-human heart.